The Four Primary Phases of a Project

The A-B-C-D's of getting from a rough idea to a happy ending

Most human-made things started out as projects. Whether it was a bridge, a new airplane design, a scientific instrument, a vaccine, a children’s book, a software application, or a space shuttle—all of these were projects at one time. They each started with a need to address a unique problem—and then they followed a common path to success.

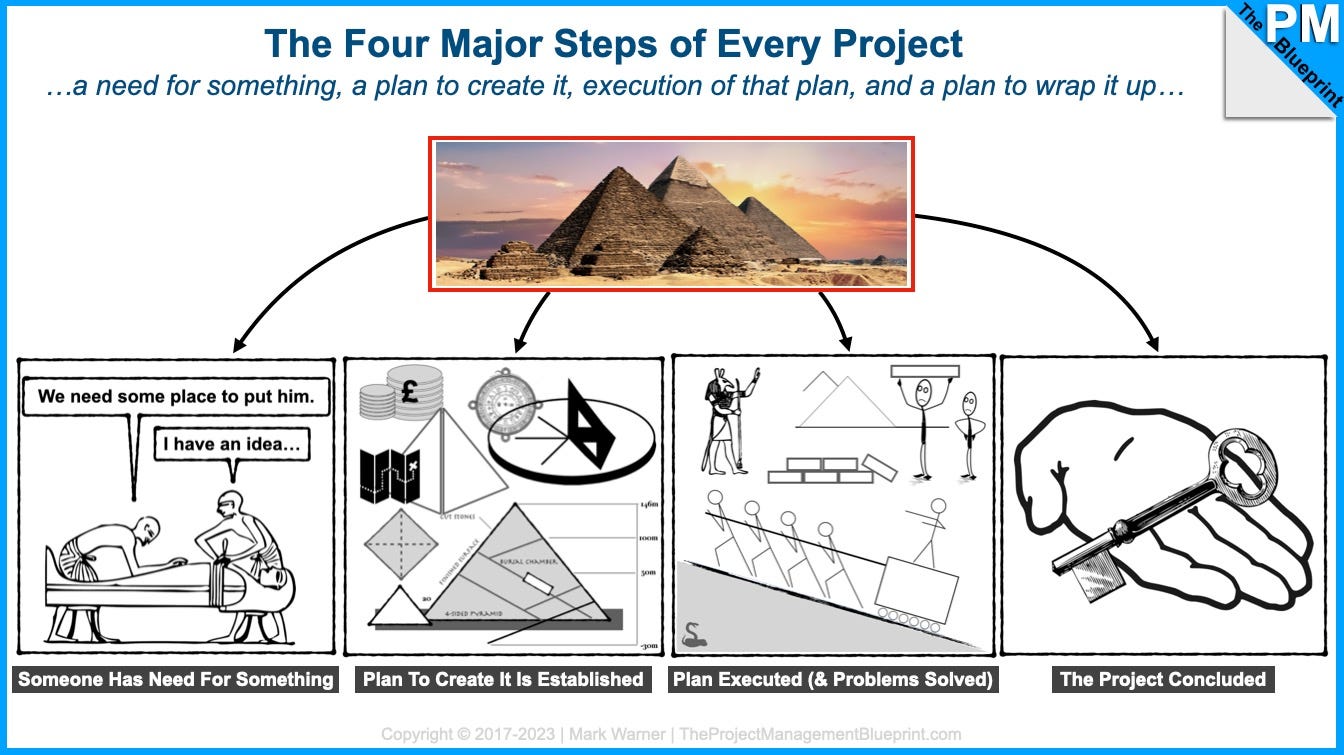

Take the pyramids of Egypt, for example. An Egyptian Pharaoh wanted a special burial place and decided on a giant pyramid of stone blocks. Someone was ordered to work out the design details, put a construction plan together, round up a bunch of workers/slaves, set up a quarry, and so on. The team then started cutting and stacking stones per the plan. They probably ran into a variety of issues along the way, but worked their way through the issues and continued making progress, checking in with the Pharaoh from time-to-time to ensure he was happy with the direction the work was going. Progress continued upward until, at some point, the builders placed the capstone, declared success, and handed the keys for the pyramid over to the owner. Voilà, a project was successfully executed.

Okay,’s a bit overly simplified, but it’s still useful. An example like this illustrates the four common stages every project goes through, from nascent idea to successful conclusion.

A. Initiation Phase:

At the start of every project, someone identified a unique problem. This lead to a proposed conceptual solution that was agreed upon by a group of relevant people. Then someone was put in charge of implementing the solution.

In formal project management terms, a stakeholder had a need that was captured in a mission statement. A scope statement was then created that described a high-level list of deliverables and requirements that addressed the need. Then the high-level details were worked out, including rough cost estimates and schedule expectations. The overall approach and obligations of the parties were captured in a project contract, or charter, which also authorized a specific named project manager to plan the project and spend money.

The Initiation Phase of a project is the primary step in which we define the big, broad brushstrokes of a project. Who is involved, what do they want, why do they want it, how much will they spend, how long will they wait, and so on.

B. Planning Phase:

In this second major phase of a project, we take the conceptual thoughts and plans from the previous step, and we develop and refine them into detailed, actionable plans.

We develop and layer on all the required details and specific information and planning necessary to execute the project. We fully define what we’ll create, how good it has to be, precisely the order and duration of tasks required to produce the thing, and a budget for creating it. We work out all the plans to create it, determine exactly what resources are required to implement those plans, establish how information will be relayed to various parties involved, and even work out how risks that threaten our ability to succeed will be identified, analyzed, and addressed.

In formal project management terms, we define the project baseline of scope, quality, schedule, and budget, and we establish the project execution plans for acquisition, resources, integration, information, and risk management.

The Planning Phase is when we convert the high-level wants, needs, and desires of our key stakeholders into actionable plans to create a specified deliverable.

C. Execution Phase:

In the third phase of a project, the detailed plans that were worked out in the previous step are now put into practice.

Work teams are organized, and the effort is kicked off. As project manager, our duty during this phase is to prioritize and direct the work, monitor progress against the plan, and make any required changes to improve the overall trajectory of the work. We also identify threats to our project, putting in place measures to reduce their likelihood of occurrence and/or their impact on us. And of course, we keep our stakeholders apprised and informed of progress, trajectory, and risks.

D. Closeout Phase:

The last step in the process is the act of project completion. We finish all outstanding work and handover the deliverable. In return, we receive some formal acknowledgment from the stakeholders that we’ve fulfilled our end of the original contract.

And during this step, we document any lessons learned we might have gathered along the way, celebrate success, and, finally, release our project team.

Cautions & Caveats:

While this pyramid example illustrates the phases of a project in simple, easy-to-understand terms, there are a few important things to keep in mind:

First, while all projects follow a similar path, the reality is every project will have variations on this basic theme. This is because reality is always more complex and nuanced than a “book” example like this one. Further, each of these steps is shown herein to be explainable in just a few paragraphs each, but we can (and will!) fill an entire book with the details and distinctions required for success.

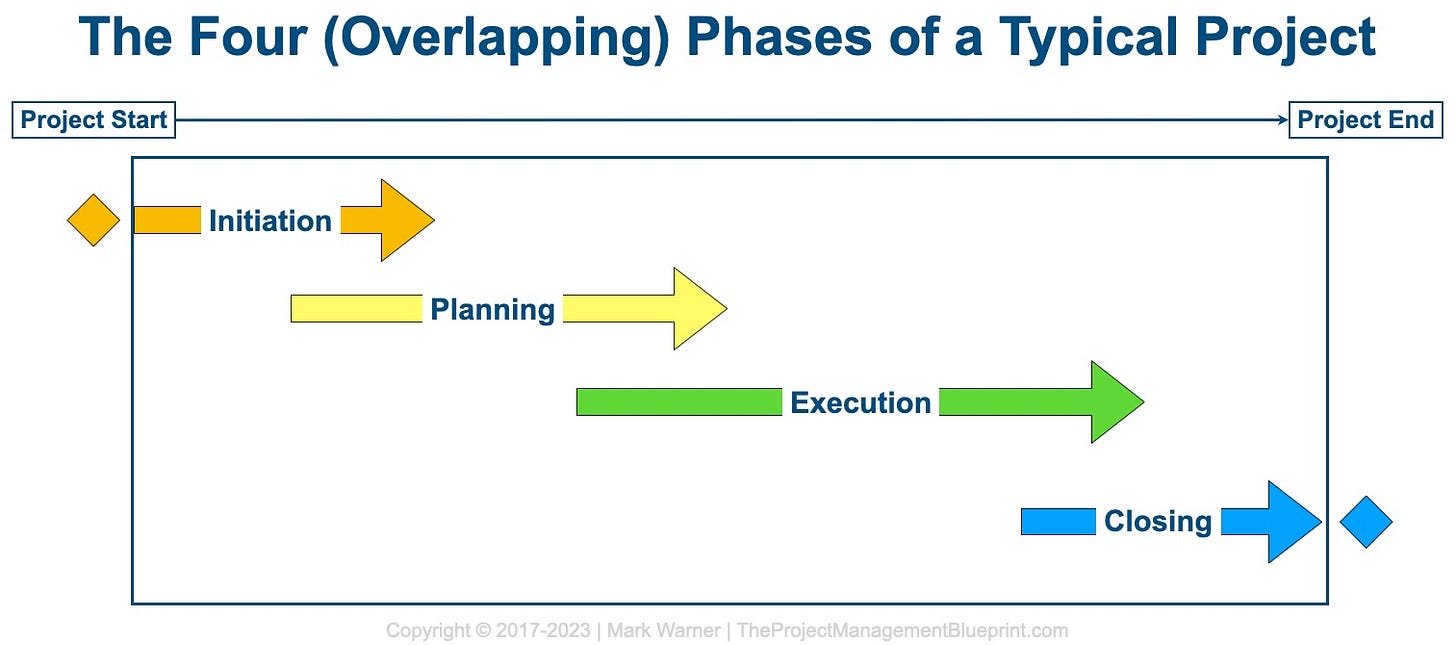

Second, the four phases are shown in a sequential arrangement, with Initiation happening fully before Planning, which occurs fully before Execution, and so on. The reality of a project is that these phases often overlap. Planning can frequently begin well before Initiation (e.g., a signed Charter) is completed. Execution (e.g., the purchase of long-lead items) also frequently occurs before the Planning phase is formally wrapped up. And Closeout not only can overlap with Execution, but you must, in fact, begin planning and setting up the Closeout phase at the very beginning of a project.

Third, there is a fifth phase that we’ll cover later that overlays these four. We’ll cover that in an upcoming description, but for now, keep an open mind that the purely mechanical steps of Initiation, Planning, Execution, and Closeout aren’t the full story. (And, no, the fifth phase is not the Project Management Institute (PMI) phase of “Monitoring and Controlling,” which, in the cold, hard reality of a real project, is just another aspect of the Execution phase.)

The Bottom Line:

Every project differs from the next one; it’s what makes them projects, and not some form of operations or manufacturing. Every project is unique—but every project also is very similar to every other one. There is a purpose, a deliverable that meets that purpose, a plan, and a resolution. More pointedly, every project goes through a series of four phases, from the definition of the purpose on through to a successful conclusion.