Standing Up a New Project

A blank sheet means a lot of work lies ahead...

This is a good-news/bad-news story.

The good news? Recently, my organization received a formal award notice (along with $19M in funding) from the National Science Foundation (NSF) for a design project. Specifically, the design of the ngGONG solar observatory network of telescopes. The stated objectives of the project are to create preliminary-level designs and specifications for the observatory and all of its subsystems, and create the components of a proposal for constructing the observatory (e.g., schedule, cost estimates, procurement plans, risk identification, etc...) It’s an exciting occasion for us, and one that we’ve been working toward for years.

But here’s the bad (or better stated, “sobering”) news: now we actually have to do the work. What was yesterday an exciting possibility on a blank sheet of paper is today a very real responsibility—and correspondingly huge set of action items. Expectations are high, and our detailed roadmap to project success is not yet fully developed. Said more simply: we now have to organize and “stand up” the project, complete the detailed plans, hire and onboard an entire project team, and then execute on time, on budget, and create all project deliverables.

With an immovable three-year deadline and fixed budget, we don’t have any free time to waste. Therefore, one of my first acts as project manager was to create an “assumptions log” (a/k/a “information document”). This is a big, living document that serves as a temporary repository for everything we know (and don’t yet know) about the project. As we progress deeper into the planning of the project, this document will serve as source material for more formal project items, such as the WBS, schedule, and budget.

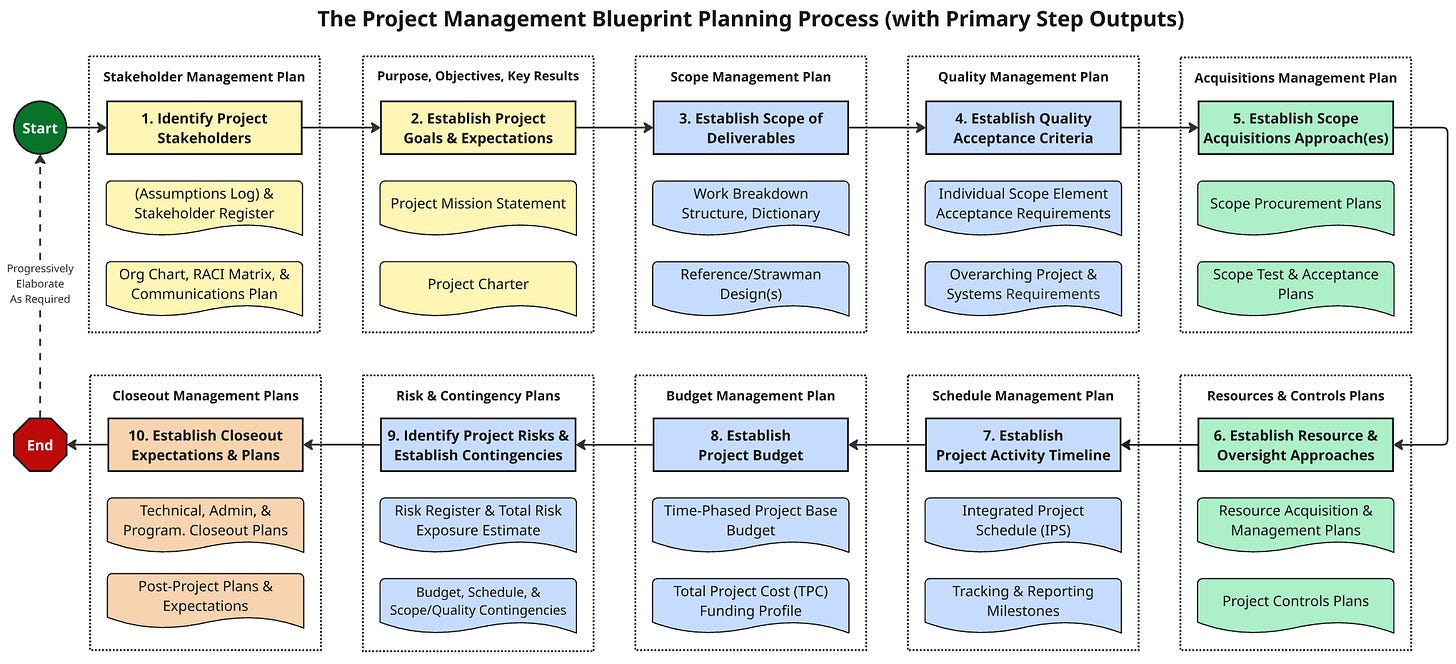

I organized this document around the Project Management Blueprint (PMB) 10-step process, expanding it with design thoughts and next-action logistics. The document acts as a “launch” device that bootstraps the project, brings new hires up to speed, and helps—from day one—to manage the expectations of both internal and external stakeholders alike. The document defines what is what (and what is not) at the start of the project.

I created the document in Google Documents (using its new “tabbed” feature, which allows one to stitch together a bunch of separate documents into a cohesive whole). I then shared the document with key stakeholders and team members, and then held a kick-off meeting with them to bring everyone up to speed, update the document with real-time feedback, and set the project in motion. (In an upcoming post, I want to dig a little more deeply into this “information” document, as I believe it’s an under-utilized, but very powerful, tool that can give you and your project an immediate leg up on the workload.)

Besides creating that document, I’ve also been working with our IT department to set up a structured project Google Drive, which will serve as a single-source-of-truth repository for all project files. I’ve created an action-item “to-do” list (using Atlassian Jira) to assign and formally track actions. Plus, I’ve created draft templates for a variety of requirements documents, organized standard meeting note formats, drafted our WBS, created a template for our monthly report to the NSF, worked with our business group to set up charge accounts and timesheet codes, scheduled a series of weekly progress meetings with the team, etcetera, etcetera, ETCETERA! The list of things needed to “stand up” a project like ours is huge, but we’re chipping away at it piece by piece. This is how elephants like ngGONG get eaten: one bite at a time.

Throughout all this initial work, discipline and standardized processes/templates are my guiding beacons. The Project Management Blueprint method that I teach is being put into practice, and it has to be more than just a list of boxes to check; it’s how I’m (hopefully) going to ensure our project foundation isn’t just solid, but adaptable enough to withstand the inevitable curveballs we know are coming our way. The process begins with getting the project organized and formally documenting project stakeholders, and then progresses through clarifying high-level goals and objectives, capturing the full scope of deliverables in a WBS, defining acceptance criteria for that scope, planning procurements of the scope, establishing resource and project controls methods, building a comprehensive integrated master schedule and a credible time-phased budget, creating a complete risk register, and even planning for closeout.

This is the first blog entry in what I intend to be a public diary of the ngGONG project. I hope to make this journey transparent—with all its ups and downs—for other project managers, team members, and anyone curious about what it really takes to launch something of this scale. The hardest part of any project is getting it off the ground the right way, and that’s exactly where this story begins.

So hang on for what I’m sure will be a host of upcoming good-news/bad-news posts! Wish us luck as we stand up this important new project!

Here for the journey! Kudos to you and the team 🎉

Looking forward to seeing this project progress! Thanks for working out loud!