Project Diary: Define, Refine, Finalize...

Progressive elaboration in project management

“The first draft of anything is s**t.” — Ernest Hemingway

Papa Hemingway’s words may be crude, but they hold the secret to creating anything complex, whether it’s a novel, a house, or a project management plan. When professional writers sit down to work, they don’t produce a polished manuscript in a single sitting. They typically start with a rough outline, move to a messy first draft, and then iterate through successive rounds of editing and polishing. Architects work the same way; they sketch the “flow” of a home and the general shapes and sizes of the rooms long before they ever think about specifying the bathroom fixtures or floor coverings. They understand you must establish the broad strokes before you can effectively fill in the details.

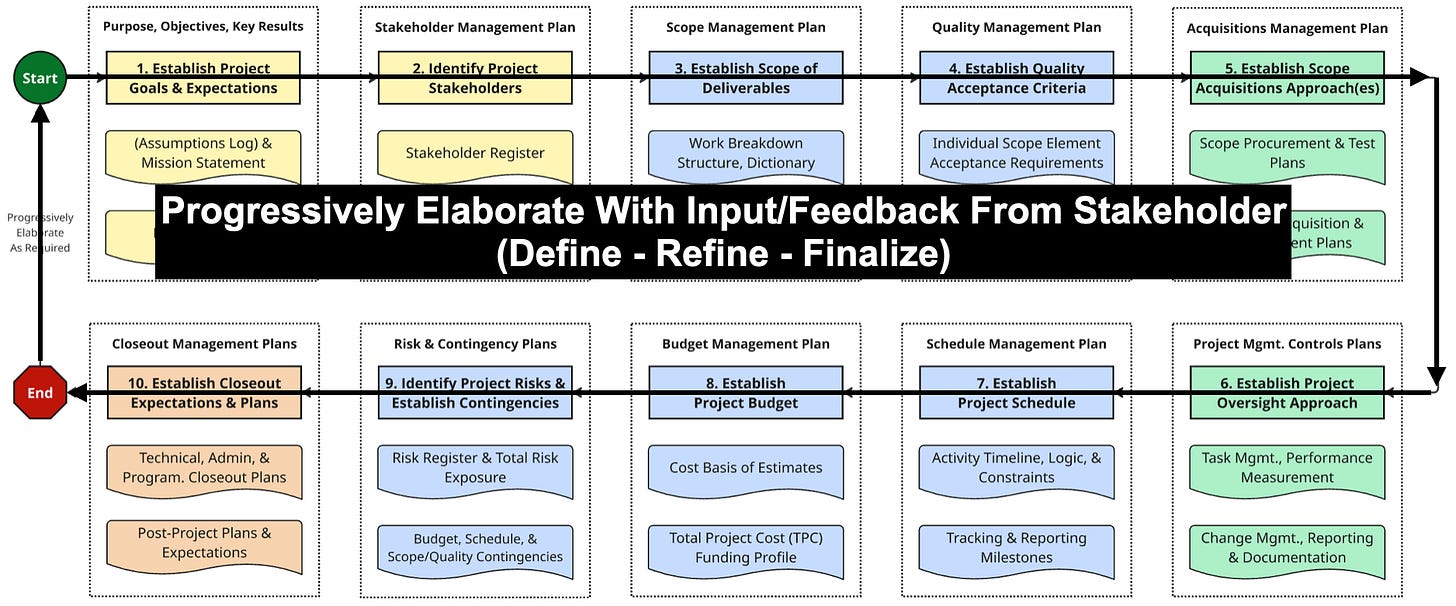

In the world of project management, we call this concept progressive elaboration. At its core, this is the practice of developing a plan in steps and continuing to increment it with better information as it becomes available. It is the acknowledgement that we cannot (nor should) know everything at the start of a project. Instead of trying to force a perfect, 100% complete plan on day one—which is a recipe for frustration and failure—we deliberately choose to define our plans broadly at first, and then refine them in a series of incremental loops. We define, then we refine, and only then do we finalize. This allows us to lock in the “big picture” direction before getting bogged down in the minutiae that might change anyway.

Why Progressive Elaboration Matters:

The primary value of progressive elaboration is that it prevents us from wasting time, money, and mental energy on “dead ends.” Imagine if an architect spent weeks detailing the tile work for a bathroom, only to realize later that the client hates the location of the master suite and wants the entire floor plan stretched and flipped. All that detailed work would be wasted. In project management, if we dive too deep into the specifics of a schedule or budget before we have even agreed on the high-level scope and deliverables with our stakeholders, we risk having to tear it all up and start over when they inevitably disagree with our fundamental assumptions.

Progressive elaboration is a critical tool for risk management and stakeholder alignment. By presenting a “rough draft” of our plans to stakeholders, we invite them into the process early when changes are cheap and easy to make. It is far easier to adjust a bullet point on a slide deck than it is to re-engineer a subsystem that has already been designed. This iterative approach allows us to course-correct early, ensuring that when we finally do commit resources to the detailed work, we are doing so with the confidence that we are heading in the right direction. It keeps the team focused on the right level of detail at the right time, preventing the paralysis that comes from trying to solve every problem at once. And perhaps most important of all, this approach all but guarantees buy-in and support from our primary stakeholders, as they feel like the designs and plans are as much theirs as ours.

How We Are Using This On ngGONG:

On the ngGONG project, we are applying progressive elaboration essentially everywhere, from the macro level of developing our management plans, to the micro level of establishing technical designs and specifications. For our management approach, we didn’t write a perfect Design Execution Plan (DEP) overnight. Instead, we started by addressing the ten steps of the Project Management Blueprint in broad brushstrokes. We asked: Who are the key players? What are the primary deliverables? What is the general timeline? What is the approximate order-of-magnitude cost? We documented these high-level answers, vetted them with our leadership, and only then began the deeper work of fleshing out the specific WBS dictionary entries and detailed bottom-up cost estimates. This aligns perfectly with the guidance in the recent NSF Research Infrastructure Guide (RIG), which explicitly calls for “tailoring, scaling, and progressively elaborating plans” to fit the maturity of the project.

Technically, we are using the same “Define—Refine—Finalize” loop for our engineering designs. An example is our work on the telescope’s light-feed system. Rather than immediately trying to engineer the final optical prescription, we first established a rough concept: an alt-alt mount on a tower. We present this concept, gather feedback, and then move to the next level of detail, such as determining the f-number of the beam and how to distribute light to the instruments. We just completed a similar loop for the creation of our Science Requirements Document (SRD). We started with a table of contents and outline, moved to a rough draft, and are now going to present that draft to our Science Working Group for input. We don’t waste time on the specifics until the big picture is approved.

How You Should Apply This:

You can apply the same logic to your own projects by resisting the urge to be a perfectionist in the early stages. When you are applying the ten steps of the PMB, do not generate final, detailed answers for all ten steps on your first pass. Instead, treat your first pass as a rough “sketch.” Identify your most important stakeholders, draft a rough scope, take a stab at the major risks, and put together a high-level timeline. Then, stop. Take this outline to your key stakeholders and get their buy-in on the general approach. Ask them: “Is this roughly what you had in mind?”

Once you have that high-level agreement, you can start your second loop. Go back through the steps and add the next layer of detail. Turn your high-level scope into a Level 2 or Level 3 Work Breakdown Structure. Turn your rough timeline into a high-level flowchart with major milestones. Then, loop back to your stakeholders again. Repeat this process until you have an execution plan that is robust enough to actually carry out—with confidence. By working in these concentric circles of detail—defining, then refining, then finalizing—you ensure that your project is built on a solid foundation of agreement, rather than a house of cards constructed in isolation.

The Bottom Line:

Hemingway was right: the first draft is far, far from perfect. In fact, it is often plain wrong, but this is okay. Progressive elaboration allows us to navigate the uncertainty of a new project by starting with what we know and systematically filling in the blanks. It saves us from costly rework, aligns us with our stakeholders, and ensures we are always building on firm ground. So, don’t write the final manuscript on day one; you can’t. Sketch the outline, get feedback, and then—and only then—start filling in the details.

I think I might use Define, Refine, Finalize for my personal goals this year -- starting with a rough picture of what I want my 2026 to look like.

This is so useful, thanks for sharing