Project Diary: Advisory Boards

Using a composition matrix to create a strong & balanced oversight group...

“Diversity: the art of thinking independently together.” – Malcolm Forbes

What is a composition matrix?

The ngGONG objective is to design a next‑generation global network of solar observatories that will replace the existing GONG system and serve research, space‑weather, and operational communities such as NOAA and the Department of Defense. The stakes are high, because these observatories will feed data into everything from basic helioseismology research to real‑time space‑weather forecasting and defense operations. That level of impact demands oversight, and one of the outside groups we need to have is a Science Working Group, or SWG. And that group needs to be both scientifically deep and broadly representative. Enter: composition matrices.

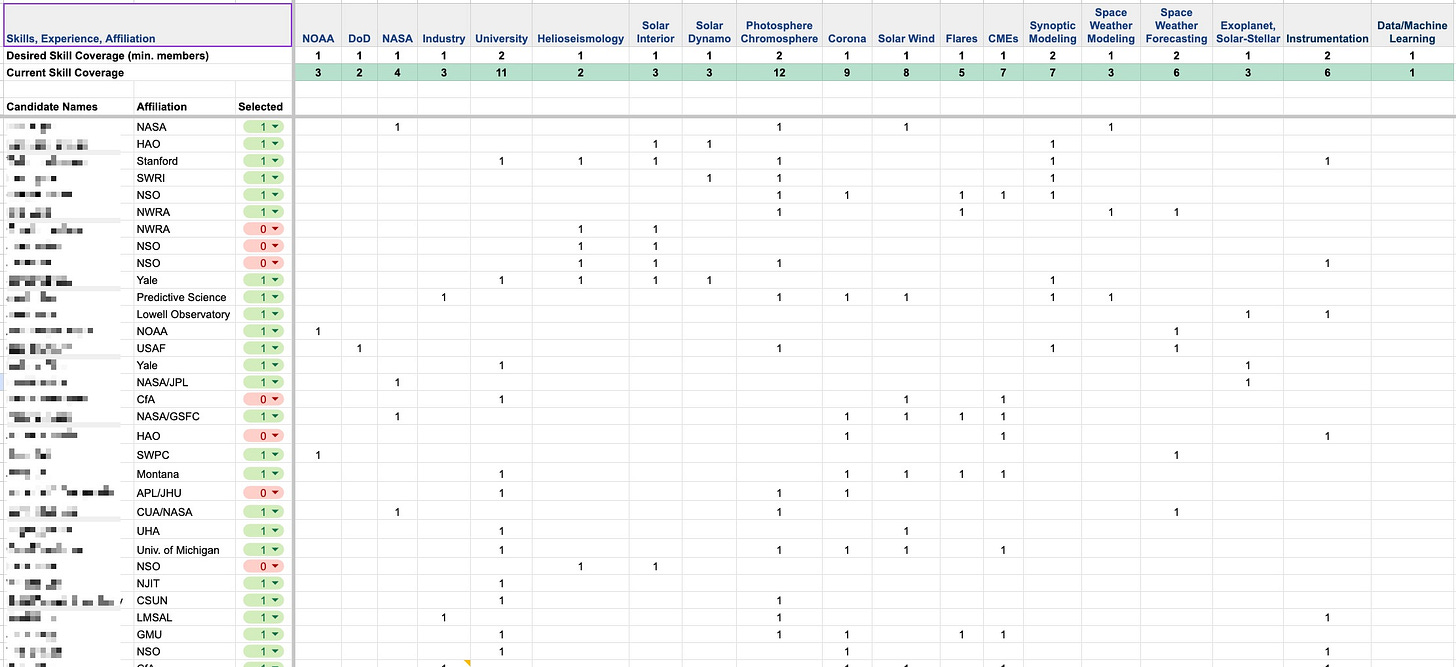

A composition matrix is a simple tool (i.e., a spreadsheet) that can be used to assemble a strong and diverse group of people. For example, it forces rigor about who sits on an oversight body like our SWG. Down one axis are candidate names; across the other are the attributes that matter for the board: institutional affiliation, domain expertise (helioseismology, solar dynamo, instrumentation, space‑weather modeling, etc.), skills, and sometimes geography or sector (NOAA, DoD, NASA, university, industry). Each cell lets you mark whether a candidate brings that attribute. When you step back, the matrix shows visually any gaps and over‑concentrations far more clearly than a mental list or an email thread ever could.

Why this matters in project management:

From a Project Management Blueprint perspective, advisory boards live at the intersection of Step 1 (Identify Project Stakeholders) and Step 2 (Establish Project Goals & Expectations). They represent key communities that care about the project’s outcome and have both influence and expertise to shape it. For ngGONG, that includes research scientists, operational space‑weather users, funding agencies, and international partners who will rely on decades of observations. Getting the mix of oversight people wrong means the project can drift away from what “success” actually looks like to its most important users.

A composition matrix converts the vague desire for “diverse representation” into something verifiable. It lets you check, for example, that you are not overloaded with photosphere experts while ignoring the coronagraph or space‑weather forecasting communities, or that you have representation from both research observatories and operational centers like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center. It also helps satisfy formal sponsor requirements: the National Science Foundation expects documented stakeholder engagement and advisory structures that cover the full performance‑measurement baseline of scope, quality, schedule, and risk.

How we’re doing this on ngGONG:

For ngGONG, the National Solar Observatory has the responsibility for defining the science objectives that will drive technical design decisions. But this science team does not want, nor is it allowed by NSF policy, to do this in isolation; the project is required to show broad community input and engagement. The answer is a Science Working Group, which is an advisory committee of roughly 10–12 experienced, external scientists and researchers who will meet a few times per year to “look over our shoulders,” review requirements documents, and advise on instrument and telescope design choices and plans.

The challenge is that there are many excellent people who could serve on such a board. To bring discipline to selection, we built a composition matrix in Google Sheets and started by populating it with dozens of potential candidates drawn from our internal knowledge—capturing their affiliations, domains (solar interior, flares, synoptic modeling, instrumentation, machine learning, etc.), and sector (NOAA, DoD, NASA, universities, industry). We then held a working session with a partner institution, asking them to add names, refine expertise tags, flag conflicts, and suggest people to rule out for practical reasons (availability, overlapping roles, or organizational balance). The result is not the final SWG group, but a curated pool from which a future SWG chair can help down‑select to a balanced 10–12‑person committee.

How you can apply this to your project:

On your project—whether you are building a software platform, a research facility, or a regional infrastructure program—the same approach scales well. Start by defining what your advisory body is supposed to do; for example: provide stakeholders’ voices, review key documents, validate requirements, or act as a sounding board for trade studies. Then list the perspectives and skills that must be present to provide these things, such as functional areas, customer types, partner organizations, regulatory bodies, and any critical cross‑cutting skills like systems engineering or operations. These become the columns of your matrix.

Next, brainstorm a list of candidate members and add each to a separate row. Do a first pass yourself, then bring in a small, trusted group of internal and external stakeholders to mark up the sheet: add names, correct expertise tags, suggest removals, and highlight potential chairs. Once you can see the gaps, you can deliberately target invitations, for example, adding someone from a neglected geographic region or a missing user segment. Finally, as on ngGONG, consider separating two decisions: first assemble a strong candidate pool; then appoint a chair who can partner with you to select the final board and keep it effective over time.

Bottom line:

A good advisory board should indeed be “independent together.” A composition matrix gives you a concrete way to build that independence and togetherness into your project from the start. It will not produce a perfect oversight committee—nothing will—but it reliably yields a stronger, more balanced board than picking names from memory or politics alone. For ngGONG, that means a Science Working Group that can credibly represent the broad solar and space‑weather communities, help NSO navigate tough design decisions, and keep a multi‑decade observatory network aligned with what the community actually needs. For your project, a composition matrix is an easy to use, but powerful, tool that can dramatically improve stakeholder coverage, governance quality, and, ultimately, your odds of long‑term success.

Really practical approach to advisory board formation. The compostion matrix solves the classic problem where everyone agrees on needing "diverse represenation" but nobody can articulate what gaps actually exist. Forcing explicit attributes per candidate turns political intuition into verifiable coverage, which is especially valuable when stakeholders later question board balance or NSF audits governance struc ture.