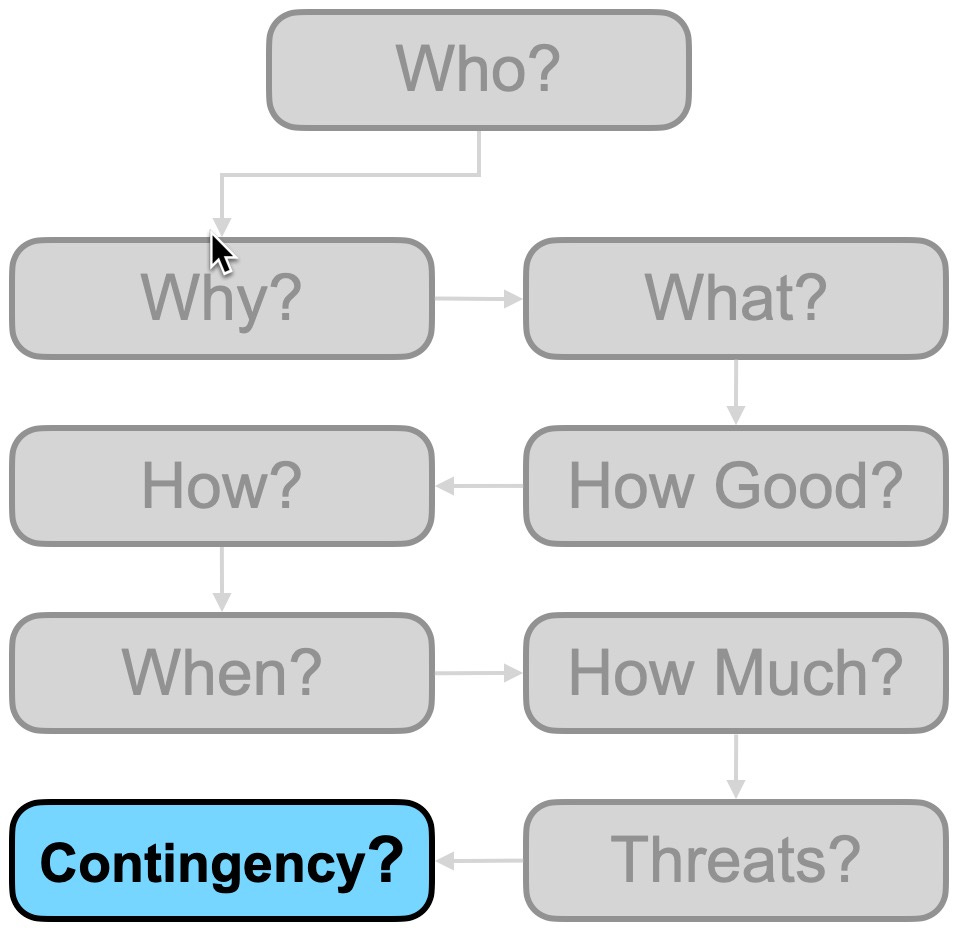

Next: Establish "Contingency"

Creating a reserve of money, time, and/or scope to cover the cost of a realized risk

In the last step, we identified negative risks (a/k/a “threats”) to our project. We also responded to those risks, striving to reduce the likelihood and/or impact of each to an acceptable level. But despite these reductions, there is always residual risk on a project. Worse, some of the residual risks will actually occur. We call this “realized” risks, or, more simply, “issues.” We need issue response plans, and, just as importantly, extra resources to cope with any issues that do arise. These extra resources are called contingency. Typically, there are four types of contingency we need to consider: budget, schedule, scope, and quality.

Budget contingency is exactly what it sounds like: extra money set aside to pay for problems as they arise. Similarly, schedule contingency is a reserve of time available to accommodate delays and schedule slips. Scope contingency is identified as deliverables that, in a worst-case scenario, may be foregone in favor of staying on schedule and budget. And quality contingency are some specific requirements (e.g., functional or performance specifications) that might be dropped in favor of one of the other forms of contingency.

Contingency is often described as the other side of the risk coin; the two are separate concepts, but are intrinsically linked. There is always risk on a project, and something invariably goes wrong. Without contingency, we won’t be able to keep our project on track to a successful conclusion. A weather delay causes us to push back a series of activities in the schedule, which then costs more money than we’ve budgeted. Contingency reserves are how we pay for these types of things as they occur.

So, how do we ensure we have sufficient contingency reserves? Let’s look at each of the four categories to see how it works:

Budget Contingency. Typically, budget contingency is a function of total monetary risk exposure. If you recall from our discussion of risk, risk exposure is the product of a risk’s likelihood (probability) and its impact if realized. The summation of all the individual risk exposures listed in our risk register is one way to estimate the overall risk exposure of the project. Ensuring our budget contingency is larger than this number is usually a good place to start in estimating how much reserve money is required. Other methods include performing a Monte Carlo analysis of the risk register or the budget. We can also use various algorithmic methods, such as risk factor analyses.

Schedule Contingency. We can estimate how many days or months of reserve we should carry by a variety of methods. The simplest of these are with standard rules of thumb. E.g., 1 day of contingency for every two weeks of project duration, or 1 month for every year of schedule. But there are also more sophisticated methods that can give more realistic estimates, such as running a Monte Carlo on the schedule, with inputs of best case, worst case, and most realistic durations for the schedule activities.

Scope Contingency. Determining which elements of your WBS might be excluded is best performed in consultation with your key stakeholders. Nobody wants to forego deliverables, but sometimes it’s the best (or only) option. The key is to establish key mission priorities with your stakeholders, and then triage the scope from the most critical to the least. A “de-scope” list is then created, along with impacts, potential cost and time savings, and so on.

Quality Contingency. Like scope, determining which requirements are less important than others is a task that requires significant input, feedback, and involvement from the customers, users, and other key stakeholders of the project. And again, the mission priorities of the project will be the key drivers of these discussions. Often, quality contingency is captured in the de-scope list.

Successful project management is about planning for the best, but also preparing for the worst. This contingency step is all about providing reserves to cover the “cost” of things when they go wrong on a project. We're not talking about padding our budgets or timelines unnecessarily; instead, we're strategically allocating extra resources—be it budget, time, scope, and quality—to allow flexibility to cover problems when (not if) they arise. It's about the balance between prepared and paranoid. By carefully establishing project contingencies, we're not just hoping for the best; we're actively preparing for success, come what may.